By Jay Shapiro

Who's seen this before?

Illustrations by Barry Blitt

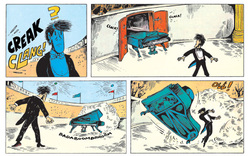

Kid’s stuff – “The Walking Dead”

Kid’s stuff – “The Walking Dead” I still see parents at Barnes & Noble leading curious children away from the comics section, telling them that they shouldn’t waste them their time and instead read “real books.” Children will always want to read comics (they are basically formatted in an ideal manner for young readers), and there’s no shortage of material, so what seems to be missing right now is that clear place in children’s media where comics belong. The idea that comics are inherently “kid’s stuff” has been eroding with the advent of the graphic novel and the cerebral work of artists like Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes. Even in popular circles, the most successful titles in bookstores are M-rated dramas like The Walking Dead and Saga.

With all that newfound respect, you’d think that the familiar scene of parents disapproving of their children reading comics would have faded away, or that children’s comics would be its own highly profitable industry. If bestsellers and critical darlings of the comic world exist in an adult hemisphere, perhaps children’s material can entrench itself in the way that matters to parents: a step on the readership ladder.

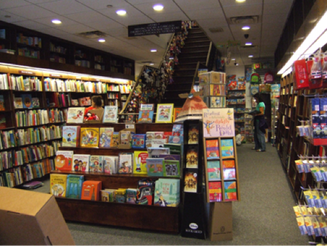

| The difference between comic books and picture books blurs with illustrators like Shaun Tan and his book, “Rules of Summer” | At Books of Wonder, a lower Manhattan children’s bookshop, I spoke with manager Scott Wong about changes in the traditional way that children transition as readers. For the longest time, parents have weaned their kids on picture books and gotten them comfortable with words until they were ready to move on to full prose or chapter books. Scott thinks that comics and graphic novels can be as a transitory tool. “Graphic novels are a great way to kind of ease that transition because kids love the idea of comic strips,” he said. “It’s always associated [with] fun reading. Sometimes chapter books tend to be a little bit more intimidating because of the amount of words. If you grew up with comic books, it’s an easy way to transition to something more challenging.” |

Scott also noticed that the kids who come in looking for comics (who, according to him, are usually between the ages of five and eight) are usually the ones guiding their parents and making their own selections.

A few blocks away at comic book shop Forbidden Planet, employee Matthew Klein echoed the idea that comics can help children develop their own preferences.

A few blocks away at comic book shop Forbidden Planet, employee Matthew Klein echoed the idea that comics can help children develop their own preferences.

Forbidden Planet is one of Manhattan’s greatest “nerd venues”

Forbidden Planet is one of Manhattan’s greatest “nerd venues” “I had a customer come in say, “I really want to get my kid into X-Men. He’s seen the movies,’ and the kid ends up walking out with something like Ghostopolis… Part of it is the rebelliousness wanting to be independent.” He said in a high-pitched voice, “I decide what I like, Dad!’ I see that wonderful independent streak in a lot of young readers, and that’s great because they want to decide what they like rather than being told what to like.”

The idea that kids can hone their ability to make their choice of reading material through comics seems fitting. After all, browsing comics is remarkably easy, even as an adult in a bookstore. Instead having to sift through the opening pages of a novel or rely on spoiler-y blurb, flipping through a comic reveals its art style, its major characters, and a good deal of the mood of the story. In the new visually oriented culture, as Matthew put it, comics are a natural fit, with series like Bone becoming huge hits.

Back at Books of Wonder, Scott did remark that some parents still discourage comic reading for their children. “Certain people don’t consider it real reading because they think of it as cartoons that they see on TV. It’s unfortunate that you see people that believe in that philosophy,” Scott said.

The idea that kids can hone their ability to make their choice of reading material through comics seems fitting. After all, browsing comics is remarkably easy, even as an adult in a bookstore. Instead having to sift through the opening pages of a novel or rely on spoiler-y blurb, flipping through a comic reveals its art style, its major characters, and a good deal of the mood of the story. In the new visually oriented culture, as Matthew put it, comics are a natural fit, with series like Bone becoming huge hits.

Back at Books of Wonder, Scott did remark that some parents still discourage comic reading for their children. “Certain people don’t consider it real reading because they think of it as cartoons that they see on TV. It’s unfortunate that you see people that believe in that philosophy,” Scott said.

Bank Street Bookstore, just by Bank Street Day Camp

Bank Street Bookstore, just by Bank Street Day Camp Uptown at Bank Street Bookstore, Regina Teltser, an employee who organizes weekly readings and discussions for children, notices those attitudes. “Some parents are really totally behind comic books. They get it: it’s just a medium. It has just as much potential for trash and great art as any other storytelling medium,” she said. “Some will be like, ‘Oh, all right, but then you have to read a real book.’ While not interfering with parent’s selections, she strongly believes comics have been helpful for certain kids, notably kids with dyslexia, or even children who are “just visually inclined.”

But, in all of this, what do parents have to say? After Regina’s Lit Talk, I spoke with some of the parents who attended. Geri Loizzo remarked that her two son (ages nine and eleven) read widely, including science books, graphic novels, and 500-page fantasy novels. “They go from these big epic things back to these shorter books,” said Geri, “but just for the sheer enjoyment of the cartoonish type thing of the comic book. They contract and they expand […] I think anything that holds a child’s interest and joy is a positive learning experience and a bridge to other types of books as well.”

But, in all of this, what do parents have to say? After Regina’s Lit Talk, I spoke with some of the parents who attended. Geri Loizzo remarked that her two son (ages nine and eleven) read widely, including science books, graphic novels, and 500-page fantasy novels. “They go from these big epic things back to these shorter books,” said Geri, “but just for the sheer enjoyment of the cartoonish type thing of the comic book. They contract and they expand […] I think anything that holds a child’s interest and joy is a positive learning experience and a bridge to other types of books as well.”

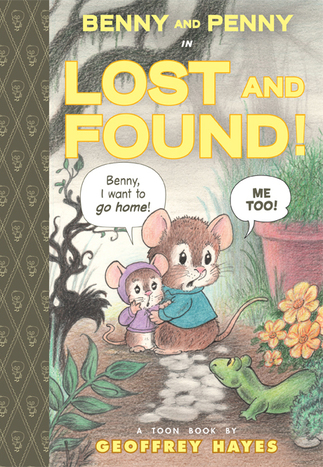

Coming this Fall from TOON Books

Coming this Fall from TOON Books While Geri’s appreciation for comics was palpable, Regina noted that the percentage of parents who approve to parents who discourage is “about 51/49.” Donna Wingate, a mother of two girls (ages eight and nine) told me that neither of her girls read comics. “It didn’t seem like it was on the linear path of reading,’’ she said. Donna added that she tried to look for books with good vocabulary and felt that comics wouldn’t really aid in that mission.

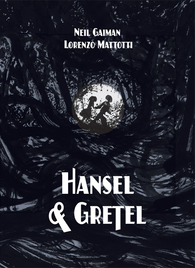

Although she and her daughters shared a mutual love for fantasy authors who have written comics such as Neil Gaiman, Donna told me that she had trouble finding comics she thought girls would like. “Frankly, I don’t know many girls who read graphic novels,” she said. “I see more of a boy interest because they tend to be action oriented.” During the interview, Donna’s nine-year-old interjected that she had little interest in comics herself, saying, “I think that graphic novels – they don’t seem to be very deep most of the time because it’s all visual.”

After the interview was over, I showed Donna the comic adaptation of Coraline, a book that her daughters had read and enjoyed. I saw both Geri’s and Donna’s kids around the store frequently, choosing their own books and the occasional copy of Amulet or Adventure Time. It seemed to me that there was less and less standing in the way of children who understood and sought out the possibilities of sequential art. Most people agreed that there were more and more benefits to children being recognized in comics. All that potential was there waiting on the shelf, and sooner or later a kid would start to browse.

Although she and her daughters shared a mutual love for fantasy authors who have written comics such as Neil Gaiman, Donna told me that she had trouble finding comics she thought girls would like. “Frankly, I don’t know many girls who read graphic novels,” she said. “I see more of a boy interest because they tend to be action oriented.” During the interview, Donna’s nine-year-old interjected that she had little interest in comics herself, saying, “I think that graphic novels – they don’t seem to be very deep most of the time because it’s all visual.”

After the interview was over, I showed Donna the comic adaptation of Coraline, a book that her daughters had read and enjoyed. I saw both Geri’s and Donna’s kids around the store frequently, choosing their own books and the occasional copy of Amulet or Adventure Time. It seemed to me that there was less and less standing in the way of children who understood and sought out the possibilities of sequential art. Most people agreed that there were more and more benefits to children being recognized in comics. All that potential was there waiting on the shelf, and sooner or later a kid would start to browse.

Jay Shapiro is a native New Yorker studying creative writing at Oberlin College and can be reached via Twitter @JayRayShapiro.