How Comics Work (Part 1) By Jay Shapiro

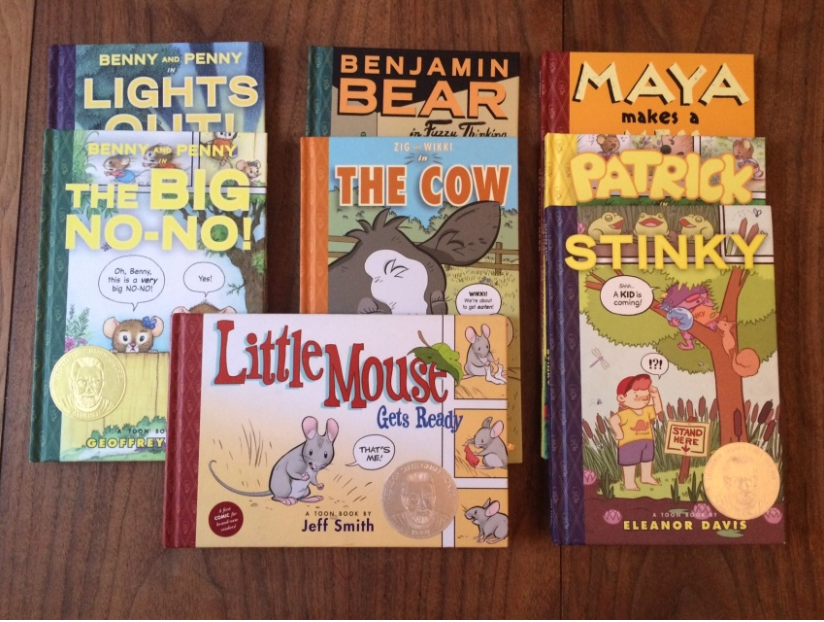

Have you ever been trapped in a children’s bookstore with seven or so kids? Well, this happened to me last month and I admit it was pretty refreshing. Not only did it remind me of how smart children are, but I also I ended up with some answers to the complex question of how we perceive stories. Children haven’t yet learned to dance around conversation topics the way adults do, so it was a great set-up. It allowed me to learn a lot and I recommend it.

Have you ever been trapped in a children’s bookstore with seven or so kids? Well, this happened to me last month and I admit it was pretty refreshing. Not only did it remind me of how smart children are, but I also I ended up with some answers to the complex question of how we perceive stories. Children haven’t yet learned to dance around conversation topics the way adults do, so it was a great set-up. It allowed me to learn a lot and I recommend it.

| I started out casually enough: the kids, their parents, and I were waiting out the rain. As the parents chatted with each other, I flipped through the comics section, loudly declaring my appreciation that the store, the Bankstreet Bookstore on 112th Street and Broadway, had a copy of Shaun Tan’s The Arrival. This attracted the attention of a curious nine-year-old, and soon enough I was surrounded, trying to explain the story–and its author’s unorthodox narrative methods–to a bunch of kids. |

Shaun Tan’s story, told entirely in pictures–with no words–opens with the protagonist saying goodbye to his family in a vaguely Eastern-European setting, as the shadows of monsters are cast over his homeland. The kids were quick to point out that he was fleeing from a dragon. I said they were probably right, but tried to explain the concept of metaphor. “It doesn’t really need to be a dragon,” I said, “In this case, it’s really just a stand-in for something bad. Let’s say for anything that can get across that idea.”

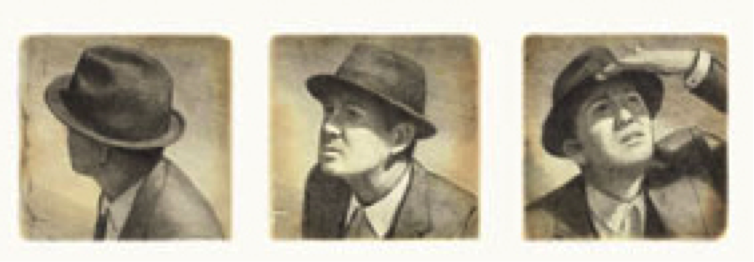

“The inspection,” from Shaun Tan’s The Arrival

“The inspection,” from Shaun Tan’s The Arrival As we went on through the book, the kids offered up their theories on what was actually happening. I told them I loved all of their ideas, but that it might be more useful to look for the emotions the story provokes rather than taking guesses at what each drawing truly represented. “If you focus on the emotions experienced by the reader,” I said, stressing that I wasn’t discouraging them from using their imaginations, “all your theories will be true because the only thing that’s absolutely critical in this story is that the main character feels alienated in his new location.”

Reflecting back now, I’m struck by two things that I want to try and explore. The first is the difference between children intuiting and inferring. How do children learn to look at parts of a situation – or in this case, story – interpret it, and infer the information around it, rather than bluntly assuming? To understand this, we first have to examine the most basic principles of a story: Recognizing details, interpreting the meaning of those details, and using that knowledge to infer the information we don’t get. This can be anything as complex as a character going through an emotional revelation brought on by eating a bagel, to something as basic as a character buying a bagel and eating it. Whether we mine away at the hidden details of prose or prick up our senses to the onslaught of information from a movie, understanding a story is dependent on our ability to use the parts to know the sum.

Reflecting back now, I’m struck by two things that I want to try and explore. The first is the difference between children intuiting and inferring. How do children learn to look at parts of a situation – or in this case, story – interpret it, and infer the information around it, rather than bluntly assuming? To understand this, we first have to examine the most basic principles of a story: Recognizing details, interpreting the meaning of those details, and using that knowledge to infer the information we don’t get. This can be anything as complex as a character going through an emotional revelation brought on by eating a bagel, to something as basic as a character buying a bagel and eating it. Whether we mine away at the hidden details of prose or prick up our senses to the onslaught of information from a movie, understanding a story is dependent on our ability to use the parts to know the sum.

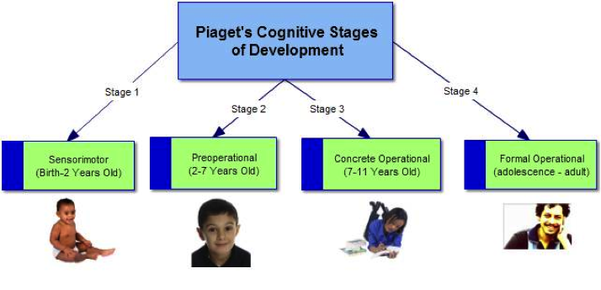

It’s no coincidence that we introduce children to reading just as they reach Jean Piaget’s preoperational stage of cognitive development. According to Piaget’s model, between the ages of 2 and 7 children begin to understand the difference between the past and the future, laying the foundation of memory, and develop the ability to associate symbols with inherent meaning. What the model also says is that kids at this stage still lack abstraction and conservation; they usually have trouble grasping ideas beyond physical situations. Going back my Shaun Tan reading, I was going over the story with kids who purportedly were past this stage–indeed they were very much in line with what Piaget calls the concrete-operational phase. They had no problem following the basics of the story, even though at the age of nine or ten, they are much more familiar with full-prose books than with silent comics. But while they accepted my broad abstract statements as interesting, they still clung to the desire to keep the story grounded in concrete facts.

When kids are below the age of 7, Piaget points out that they do not infer conclusions from lots of tiny parts, while the kids I was with were clearly past that stage. How does this apply to reading, and more importantly, why is this so critical to comics?

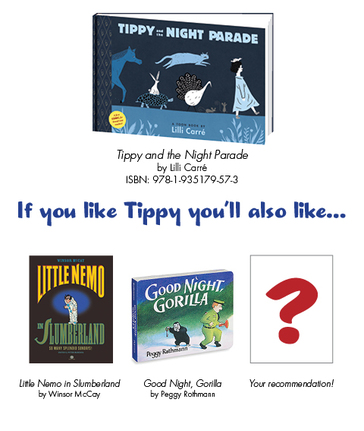

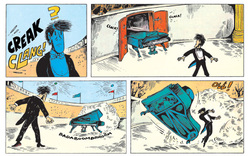

From Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud

From Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud In chapter three of Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud elaborates on how comics utilize one mental skill more heavily than any other medium: closure, or “observing the parts, but perceiving the whole.” As McCloud points out, we use closure every day as a mental compensation for the shortcomings of our senses. When you talk on the phone and assume that your friend on the end of the line still has a physical body, you’re using closure. It’s why children in the preoperational phase fantasize that the world goes away when they close their eyes; they base their inferences on intuitive reasoning, not logical reasoning. Reading words is as dependent on closure as any aspect of our lives: once we are able to recognize the full meaning of a sentence, all the sentences together to help simulate a real life experience from only a description of such. But, as McCloud puts it, “Comics is closure.”

What exactly does that mean? In one case, it would suggest that comics are made up of closure methods instead of relying upon them. A series of static images is presented and readers must rely upon their knowledge of cause and effect to infer what has happened in between the spaces. Closure in comics is used to fill in the gaps of the story, rather than make the simulation of life more convincing as in written word. It’s startling to me that many parents think that good books for children are gauged by vocabulary size–I now see that the level of abstract representation in a book is what makes it good fodder for a young mind.

Knowing all of this, let’s re-evaluate the idea that comics are easier to read than “real books.” When those kids – most of whom already trained to read chapter books – were presented with The Arrival and asked to follow only pictures, and all these pictures can be interpreted both factually and metaphorically, were they not asked to work harder than when reading an ordinary book of prose? I think so. The silent comic, and the visual part of any comics have much more room for interpretation by the reader than a story told in prose.

And if it that’s true, maybe comics are one of the best tools we have for teaching inference, for encouraging young readers to go back and forth between literal and metaphoric meaning when they read. In comics, reading is not about following instructions–it’s about creating meaning; comics force you to fill in the gaps in the narrative, just as children learn to fill in the gaps of the world they see.

And if it that’s true, maybe comics are one of the best tools we have for teaching inference, for encouraging young readers to go back and forth between literal and metaphoric meaning when they read. In comics, reading is not about following instructions–it’s about creating meaning; comics force you to fill in the gaps in the narrative, just as children learn to fill in the gaps of the world they see.

In part 2, I’ll explore the other thing kids do with the knowledge they acquire when reading comics: they imagine their own stories. Jay Shapiro is a native New Yorker studying creative writing at Oberlin College and can be reached via Twitter @JayRayShapiro.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION |